Rheology is 有趣 (yǒu qù): Our Eco-Friendly Wishing Lantern

Behbood Abedi | Andrew Janisse

January 27, 2025

In this series, we take a cursory exploration of some of the fun, and perhaps unexpected, activities around us that involve rheology!

During the Lunar New Year, sky lanterns are released to symbolize the letting go of the past year’s troubles and welcoming new beginnings. The sky lantern tradition is thousands of years old, spreading from Buddhist Monks in the 2nd Century to modern festivals in China, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. Through the years, the lanterns themselves have evolved from traditional bamboo and rice paper to modern offerings with synthetic materials. Often modern materials are considered more durable but with traditional lanterns still in use, we wanted to put our assumptions to the test with materials characterization and see if modern lanterns outperform traditional ones.

We ordered traditional eco-friendly lantern materials and a commercially available modern lantern and put on rheology and thermal analysis hats for a quick exploration of traditional and modern sky lanterns.

Rheology and Thermal Analysis: The Dynamic Duo

When rheology, the study of flow and deformation, teams up with thermal analysis like thermogravimetric analysis, they become the ultimate problem-solving duo. Together, they can:

- Diagnose Material Behavior: Understand how materials behave under different conditions.

- Optimize Processes: Improve manufacturing processes by predicting how materials will perform.

- Ensure Quality: Guarantee that materials will hold up in real-world applications.

In short, they combine their superpowers to make sure materials are up to the task, no matter the challenge!

DMA: The Fitness Test for Materials

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) is like a fitness test for materials, measuring how they stretch, bend, and bounce back under different temperatures and forces. It’s all about understanding a material’s flexibility and strength. DMA applies a wavy (sinusoidal) stress to the material and observes how much the material deforms. This helps determine the storage modulus and the material’s elastic behavior. A higher modulus means a stiffer material, and elasticity means how well the material can return to its original shape.

TGA: The Ultimate Weight Watcher for Materials

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) tracks weight changes over time, usually as a function of temperature. This instrument can tell us many important characteristics of a material such as: thermal stability, moisture content, and relative stability under different atmospheric conditions. TGA measures the decomposition temperature of materials by continuously recording the weight of a sample as it is heated. Any loss in weight indicates the release of volatile components or decomposition of the material. The data is plotted as a TGA curve, showing weight loss as a function of temperature. The point at which a significant drop in weight occurs can be identified as a decomposition temperature.

Rice vs. Synthetic Paper

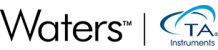

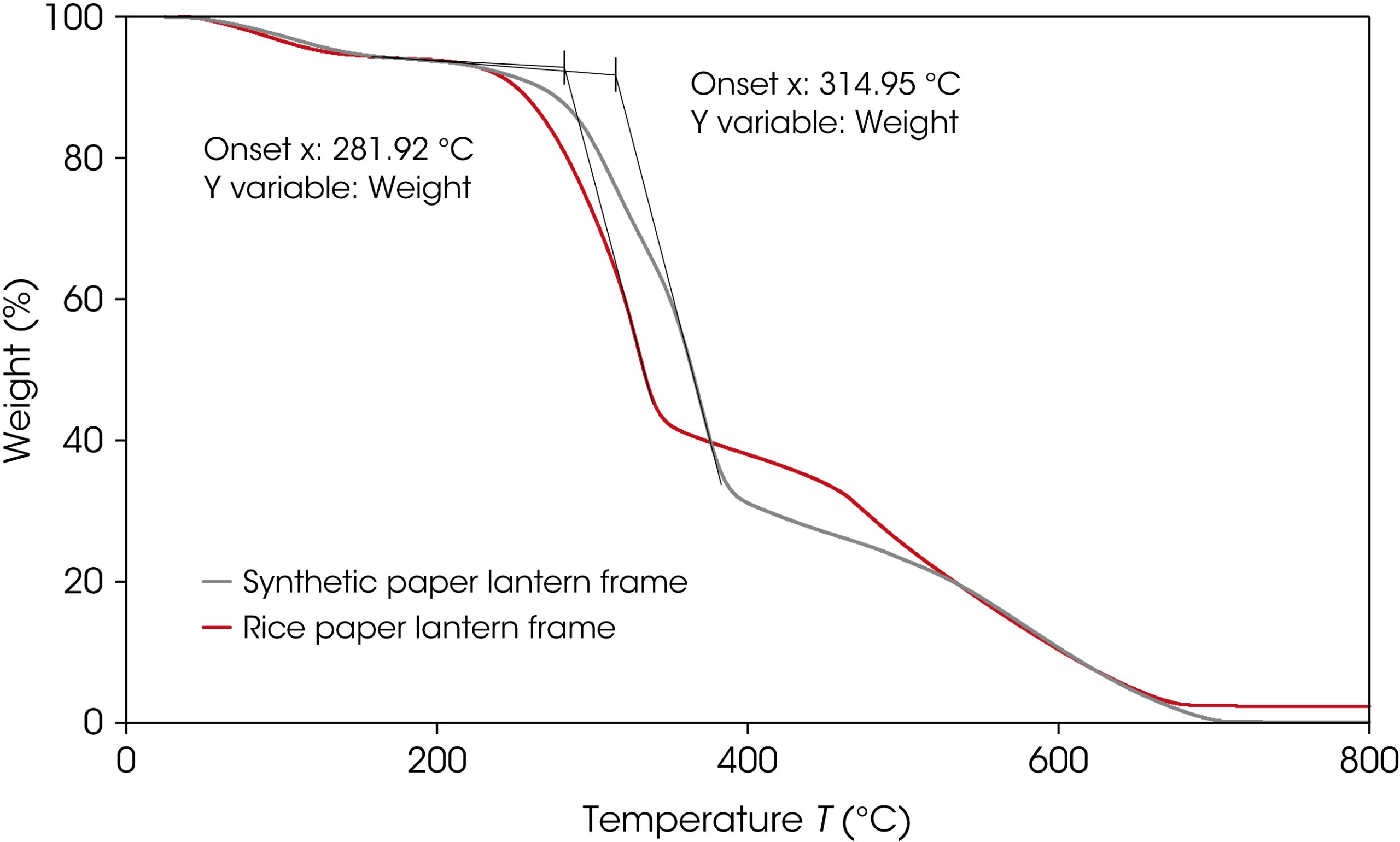

We ran TGA tests using our Discovery™ TGA 5500 for both traditional rice paper and modern synthetic paper. The test was done in air using a 50 °C/min rate to mimic the real situation where the candle is lit and rapidly heats up its surrounding air and then the papers. We observed that the onset of decomposition temperature is around 100 °C higher for rice paper than the synthetic paper (See Figure 1), which is a win for the traditional lantern! This means better thermal stability and that our wishing sky lantern can fly higher.

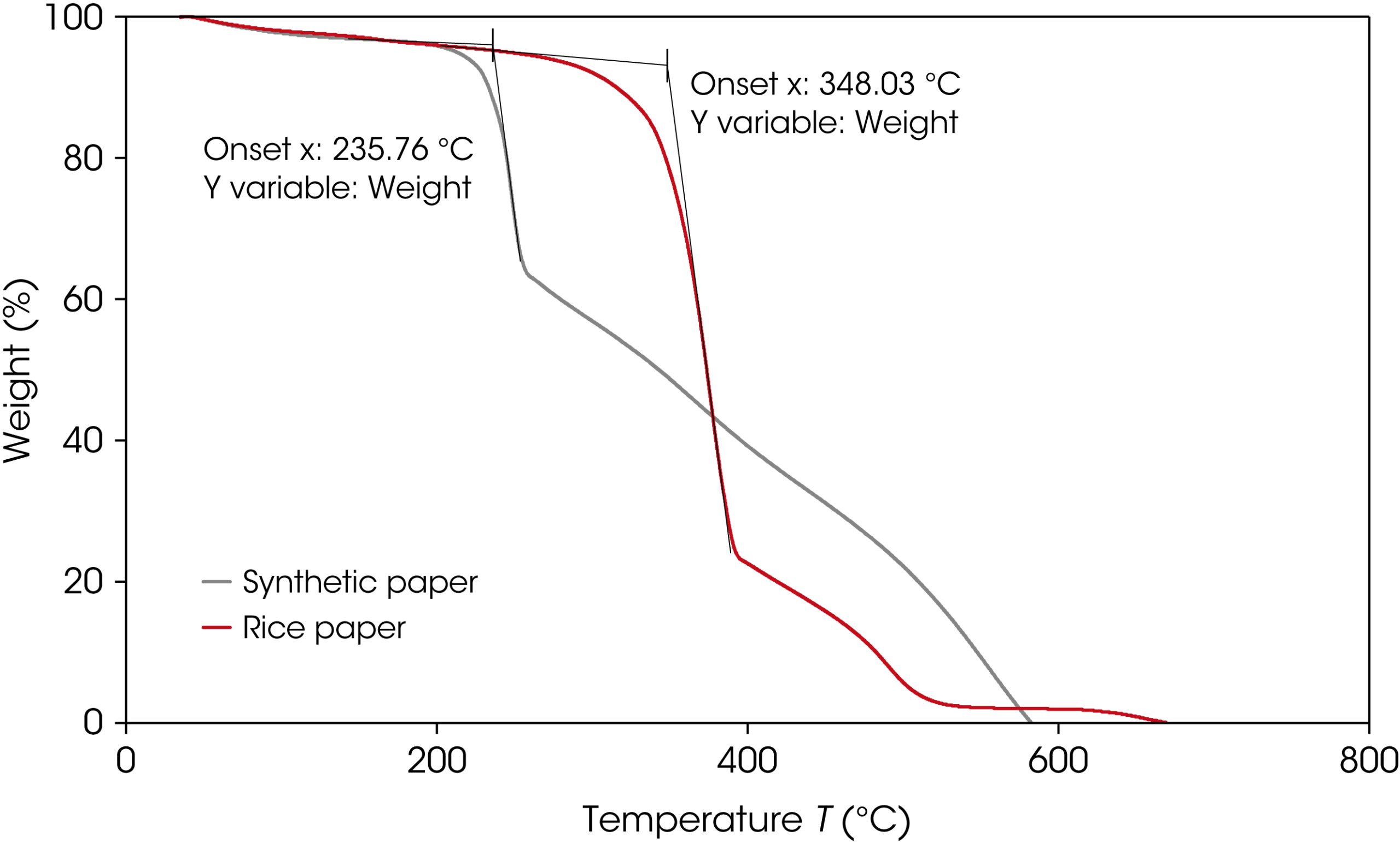

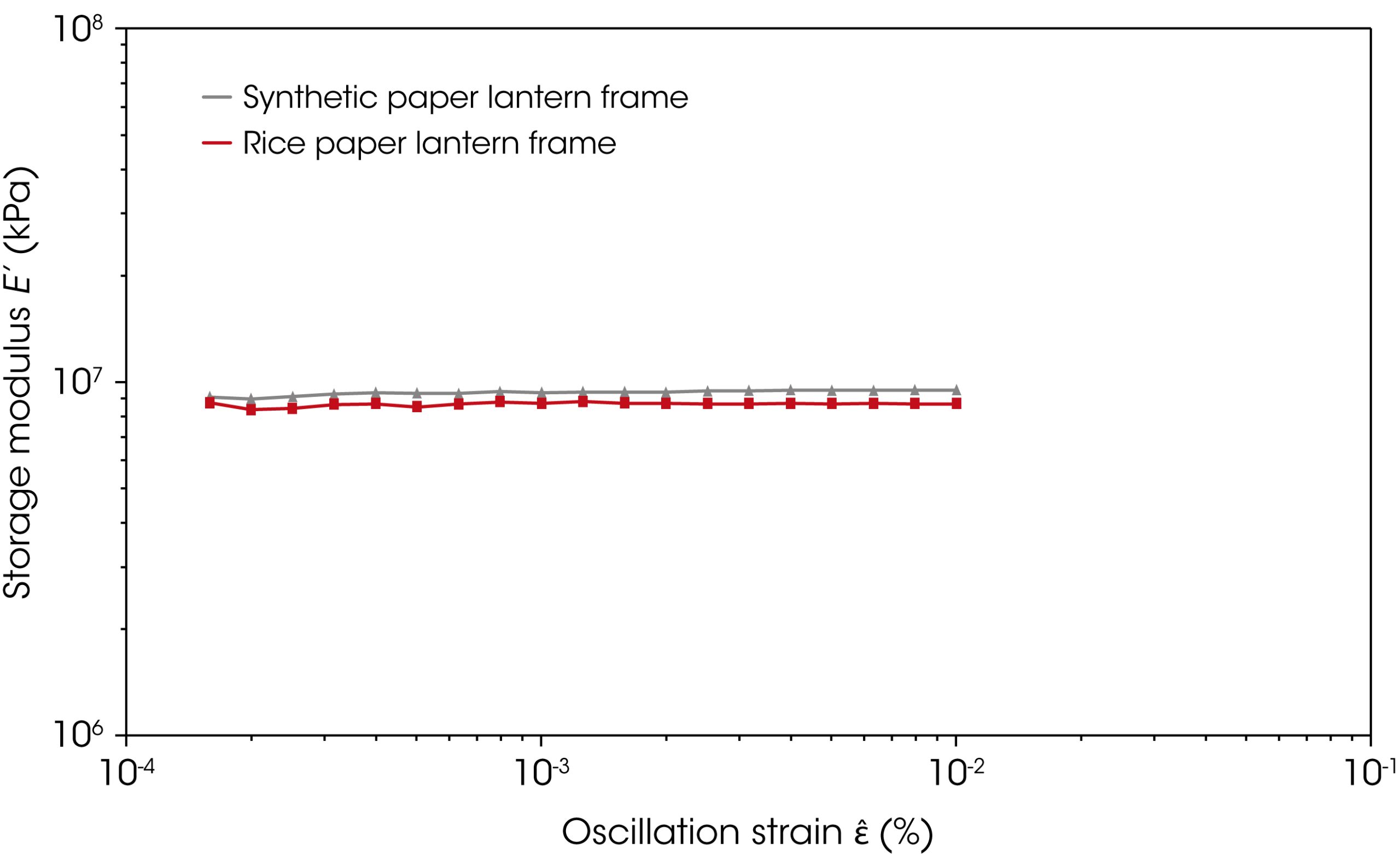

Using our Discovery™ DMA 850, we conducted an oscillatory frequency sweep test under tension. We ensured the material was within the Linear Viscoelastic Region (LVR) by performing a strain sweep test. This helps identify the critical strain beyond which the material’s response becomes nonlinear. In the LVR, the material’s structure remains intact, and the measurements reflect its true viscoelastic properties without causing any permanent deformation. We applied a sinusoidal strain to the material at a constant amplitude and gradually changed the frequency from low to high frequencies. We calculated the storage modulus (G’). We observed that rice paper shows higher stiffness than synthetic paper which means the material is more resistant to deformation under an applied stress (tension). (See Figure 2) – meaning traditional lanterns are more likely to stay intact under stress.

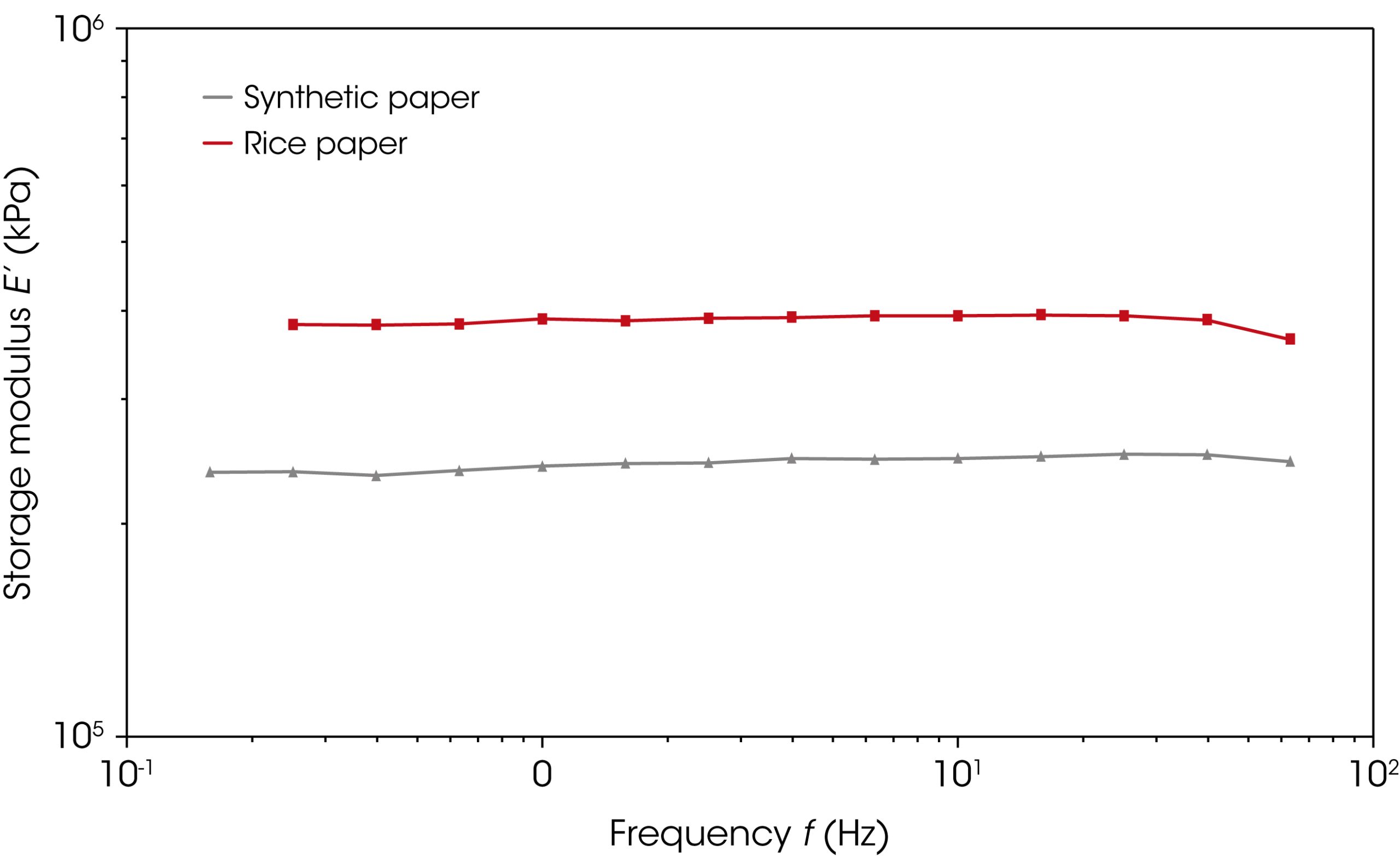

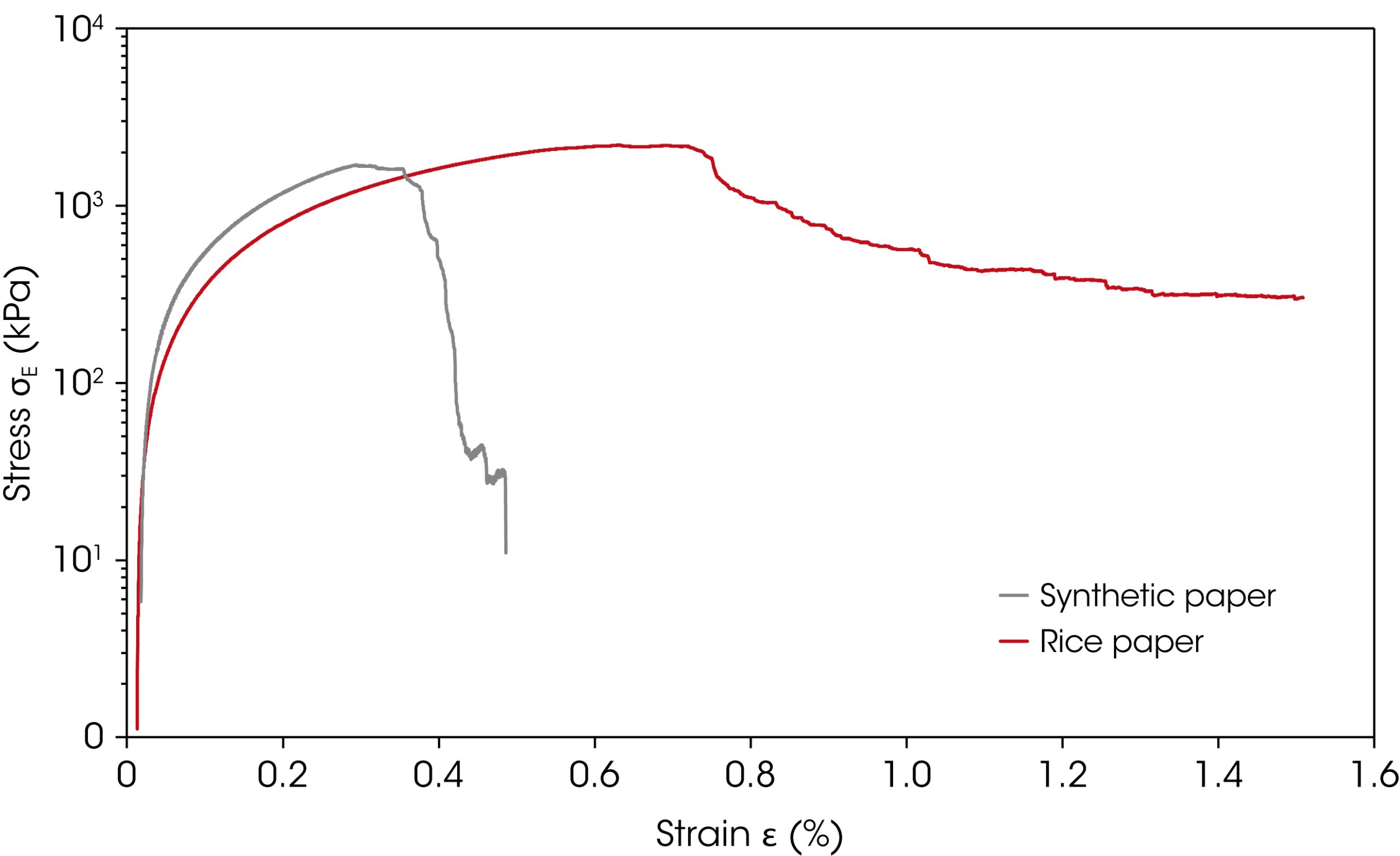

We could say the stress-strain curve is a material’s storyline, telling the story of a material under stress. That’s why we constructed the stress-strain curves of these two papers (see Figure 3). In a typical stress-strain curve, at the start, stress and strain are proportional. The material behaves elastically, like a rubber band. Then it reaches the elastic limit followed by the yield point, which is the maximum desired about of stress before deformation is permanent and the original shape cannot be returned to. Next comes the ultimate strength point: the material reaches its maximum strength. Finally, at the fracture point, the material breaks. The end of the storyline.

At room temperature, we found that the yield point of rice paper is slightly higher than that of synthetic paper. This result indicates that the rice paper can withstand greater stress before it begins to deform plastically. After the yield point, the stress values decrease for both papers, but interestingly even up to 8% strain, there is no clear fracture or rupture point. The fibers in these papers hold the pieces together, enduring significant strain and stretching considerably.

Next, we wanted to see how the candle’s flame would impact the different papers over the flight time of the lantern. The candle’s flame temperature can reach up to 1000 °C. Within 10 to 25 cm from the flame, where the rice paper and bamboo frame will sense the heat, the temperature can range from 50 °C to 100 °C when we light the candle. After a few minutes, it can rise to between 200 °C and 250 °C. This is the critical time we need for our lantern to ascend as high as possible, just below the decomposition temperature. Therefore, we repeated the stress-strain curve at a constant temperature of 200 °C to observe the behavior of these papers when the lanterns are glowing, getting hotter, and rising higher.

What we observed in Figure 4, similar to Figure 3, is that the yield point is slightly higher for rice paper. More interestingly, even at 200 °C, the natural fibers of rice paper prevent the pieces from tearing apart completely; there is no clear rupture point. However, for the synthetic paper at 200 °C, unlike at room temperature, a clear rupture point is observed below 0.5% strain. These lanterns may never experience such strain values at normal conditions, but these results reassure us that if the commercial lantern can do the job at 200°C, our traditional one will perform even better, ensuring there is no risk of ending its journey.

Lanterns’ Frames

While the paper is a key part of the sky lantern, we can’t forget about the frame holding everything together! We acquired some bamboo for the frames, selecting a thinner option than the modern frame so the lantern would be lighter weight. We also aren’t sure what the material is used for the thicker, modern frame. But would this thinner bamboo exhibit mechanical properties as good as the modern frame? So, we went back to our trusty Discovery™ DMA 850 for some tests. We conducted bending oscillatory tests to measure the storage modulus of our thin bamboo frame and compared it to the modern one.

First, we ran a quick TGA test, similar to our previous one, to observe the decomposition temperature. Both frames showed decomposition temperatures close to each other and above 250°C, which was reassuring as they will both withstand the heat of the flame. (See Figure 5).

Figure 6 shows that despite the different thicknesses of the frame samples, the flexural (bending) modulus of both frames is very close, indicating similar stiffness through bending.

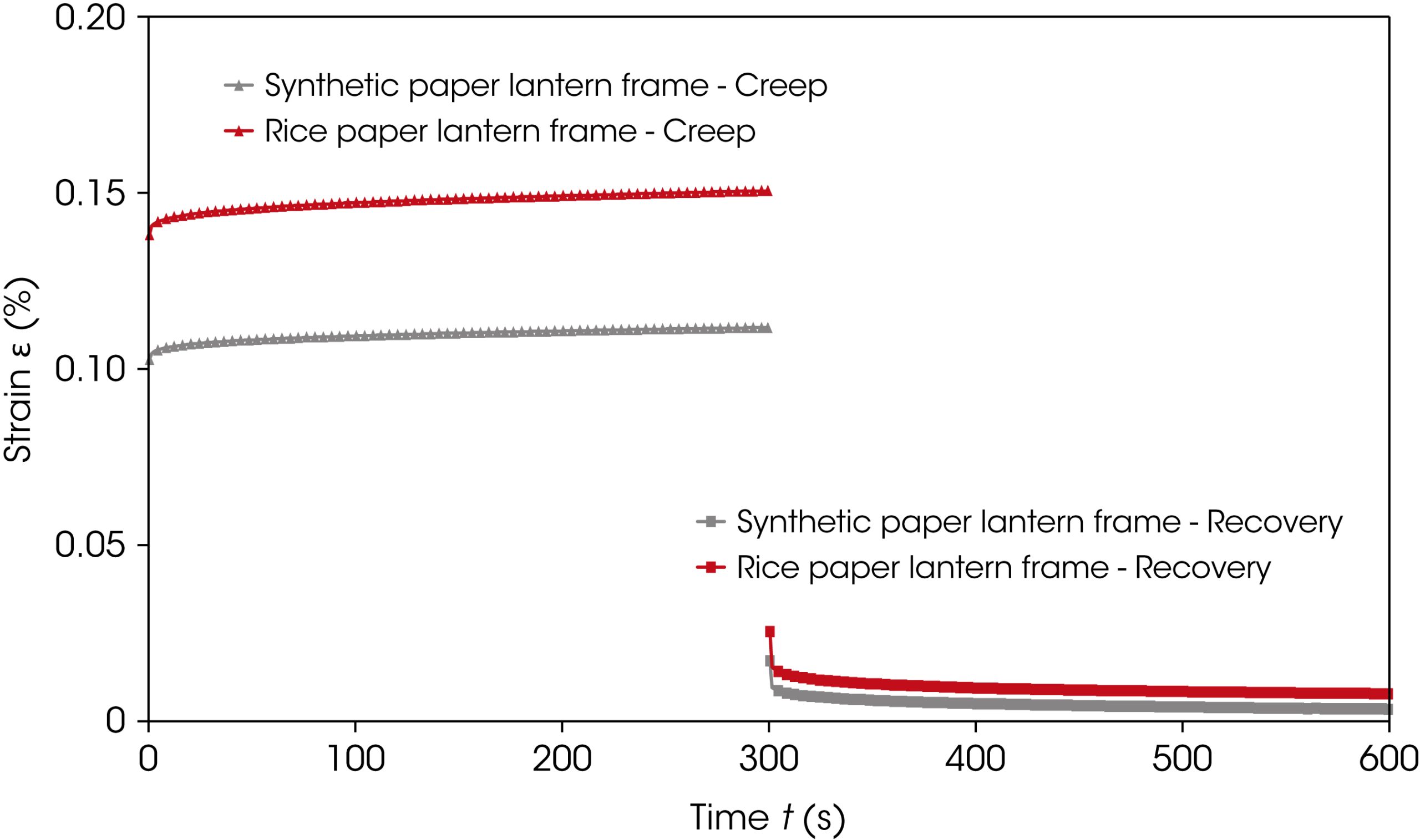

To ensure that our thinner frame would perform as well as the thicker frame of the modern lantern, we conducted creep-recovery tests on both frames.

The Creep Recovery test is like the material’s endurance challenge. Here’s how it works: A constant load or stress is applied to the material. The material deforms over time, and this deformation (strain) is recorded, creating a creep curve. The applied stress is then removed, and the material’s ability to return to its original shape is measured, creating a recovery curve.

This test is useful for predicting how materials will perform under long-term loads in real-life applications. As expected, the thinner bamboo showed higher deformation in the creep tests. However, the recovery part was impressive, as it recovered almost as well as the thicker frame. This means that even with a thinner bamboo frame, a traditional lantern would sustain the journey to the heavens (See Figure 7).

A Journey of Hope and Unity

Making a sky lantern involves crafting paper, frame and attaching the heat source, and ensuring it is safe to release. We found that traditional lantern materials are certainly up to the task! Even after thousands of years of materials innovation, traditional lanterns from rice paper and thin bamboo can fly just as long and high as newer lanterns. From their historical roots in ancient China to their role in modern celebrations, sky lanterns continue to captivate hearts and inspire reflection. As they float into the sky, they remind us of the power of shared human experiences and the universal desire for peace, prosperity, and new beginnings, making them a cherished tradition during the Lunar New Year and beyond. Have you ever participated in a sky lantern festival or released one yourself?

Other Resources

- eBook – Essential Polymer Material Analysis Techniques for Scientists, Researchers, and Engineers

- Brochure – Sustainable Polymer

- Application Note – Introduction to Dynamic Mechanical Analysis and its Application to Testing of Polymer Solids

- Application Note – Effect of Thermal Degradation on Polymer Thermal Properties